Which brings me to the shape of the stills. In the distillation process, the fermented liquid is boiled in the stills and is condensed via 1 of 2 ways. The traditional way is called a "Worm Tub" and is a long, curving pipe that passes through cold water. The more modern way is a large pipe containing smaller tubes full of the cold water. The distillate evaporates through the large pipe, passing the cooled tubes.

I'm not even going to touch whether or not the Worm-Tub is the best way vs. modern technology...not yet. I'm looking at the shape of the still themselves.

The list goes on, and on, and on...

There are MANY shapes, from pears to onions, Lanterns to lamps, extra tubing or purifiers, the list goes on. Then does the pipe that carries vapor exit at an angle or vertical? Perhaps and downward angle?

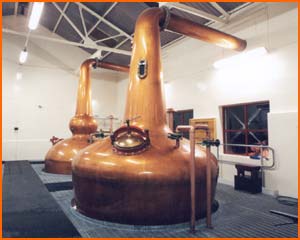

Firstly, scotch whisky stills are made of copper. Copper is popular because it is easier to work with, absorbs sulphur and yeast from the mixture (undesirables in a finished product), reduces bacterial contamination, and is an excellent temperature transfer.

Now the shape, oh the shape. What a wicked web we weave. There is much speculation about what the shape does for the finished product, but it is all anecdotal; nothing proven by science and/or experiment. Taller still are argued to catch much condensation before it exits, causing it to fall back down for a second distillation known as "reflux." Because of the "redistillation," taller still are said to have a more delicate flavor (much like the triple distilled Lowlands). Conversely, a short, fat still is said to be oiler, fuller, and richer. Some distilleries have been known to take extreme measures when replacing a still to keep the original shape. If the original still had a dent, the new still would be created with the same dent in the same place.

How can we tell? Well, certain regions all have the same basic shapes and, as we know, regions tend to have similar flavor profiles (mostly). Aaaaaannnnnndddddd the distilleries tell us so....

But I think there are some more practical reasons. Firstly,since many of the distilleries did not begin large, the space was limited. Many of the original still were shaped to fit in a small farmhouse. Tall ceiling but little floorspace? Tall and skinny. Basement with low ceiling but lots of floorspace? Short and fat. Also, the original still were made by the local coppersmith. He had a certain way of doing things, so all the still in the area would resemble one another.

The only way to know is to take an established distillery and still and completely change the still without changing the liquid or process. However, which master distiller will waste an entire batch of perfectly good whisky on a silly thing like that? (none).

Does this mean there is nothing to the tradition? Of course not. I just think that maybe there's a mystique about the stills that is more fun to perpetuate. From The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a classic John Wayne Western movie (SEE IT),

"When the legend becomes fact, print the legend."

Slàinte mhath!

No comments:

Post a Comment